| ALL |

|

ARTS AND CRAFTS

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Although the Arts and Crafts movement dominated England between the years 1860 and 1915, its effects were felt around the world, especially in Western Europe and the United States, well into the 1920s. Artwork associated with the Arts and Crafts movement is characterized by a handcrafted aesthetic that embodied the principles of its English founders: C.R.Ashbee, W.R. Lethaby, and William Morris, among others. The philosophy these men advocated centered on their belief that the Industrial Revolution had produced substandard goods with little artistic merit. In response to this situation, they sought to reintroduce handmade products to the arts and to elevate the craftsman to a more prominent position in the design professions.

In refocusing the production of art away from machines and toward individual designers, Arts and Crafts leaders hoped to reform society by changing the way art was created, patronized, and appreciated in English society. The Arts and Crafts movement promoted the idea of truth in architecture, meaning that a building should clearly express its structure, function, and material. An uncluttered exterior and interior, without applied decoration to obscure the structure, was considered the ideal, partly because the aesthetic was easily achieved without machines. This idea of truth and clarity in architecture contrasted sharply with the Victorian aesthetic currently in vogue in England in which elaborate and ornate decora-tions, usually multicolored and machine-made, dominated architectural design. Ashbee, Lethaby, and Morris believed that Victorian interiors hid truth and clarity from the viewer by obscuring the forms and shapes of a building. To this end, the simpler aesthetic of the Arts and Crafts returned truth to architecture and contrasted with the “false” art created by the machine.

The idea of a simple aesthetic had regional, national, and historic overtones. Leaders of the Arts and Crafts movement argued that the corrupted state of artistic production resulted from the negative influence of industrialization on Western, particularly English, society. Therefore, artistic production could be reformed by reviving methods of art and craft that predated the industrial era. As viewed by the Arts and Crafts founders, the period that best exemplified the preferred mode of artistic production was the age of English medieval architecture. Not only did English medieval architecture fully embody the Arts and Crafts ideal of a simple and truthful aesthetic, but buildings of the style were local and easily available for study. Most important, the forms of English medieval structures were already synonymous with the English architectural identity, and therefore reviving English medieval art and craft promoted the English national identity through architectural form. In using English medieval models, Ashbee, Lethaby, and Morris made direct connections between the past and the present and between the historic and the modern to make the Arts and Crafts aesthetic pertain directly to England. The use of English medieval models also embodied the vision of craftsmen working for a truthful aesthetic, which Arts and Crafts leaders strenuously advocated. In general, English medieval structures had been constructed by laborers who worked with hand tools to build a collective monument from honest artistic labor. Ashbee, Lethaby, and Morris argued that because the work of these craftsmen was not mass-produced, it had not been corrupted by the machine. Therefore, English medieval models served as examples of how the individual craftsman could enhance the design of an aesthetic masterpiece by ensuring that every part of the design received individual attention and that every form was designed and created by hand.

Ashbee, Lethaby, and Morris envisioned groups of craftsmen, metalworkers, stonecutters, and carpenters working together toward a finished product that combined a variety of different media. Inspired by these medieval models, Arts and Crafts leaders believed that artistic production could separate itself from the mechanized methods of the Victorian age to create a detailed and truthful expression of its time and place. Attention to detail resulted in an idea that was fundamental to the Arts and Crafts movement: that of a total work of art.

The Arts and Crafts aesthetic was not limited to any one particular medium; in fact, Ashbee, Lethaby, and Morris argued that all arts should be used to create a complete effect such that the whole became more than the sum of its parts. Every aspect of an Arts and Crafts interior or structure, whether it was art or architecture, was considered relevant to the design, and in this way the entire environment was subject to consideration by a designer or a design team. To this end, many Arts and Crafts workers began to experiment with processes that machines had performed for decades, and crafts such as fabric dyeing and printing experienced a renaissance as new methods were investigated and new objects produced.

Because the Arts and Crafts movement is a movement largely of ideas, it is difficult to single out particular designers or works, or to identify particular forms as characteristic of the Arts and Crafts style. In terms of architecture, Philip Webb’s Red House, in Upton,Kent, commissioned by Morris in 1859, serves as one outstanding example of Arts and Crafts architecture in England. Taking its name from its red brick construction, the design of the Red House avoided all decoration that recalled a direct model and instead followed the functional needs of Morris and his family. Murals, wall hangings, tapestries, and wallpapers together created a homey and medieval ambience through natural motifs that included animals, birds, flowers, and trees, all of which were native to the area or to England. Designed and crafted by Morris, his wife Jane, Philip Webb, and Morris’s friend Dante Gabriel Rosetti, the Red House expressed a relaxed and informal medieval atmosphere where different artistic media conveyed a total aesthetic.

Arts and Crafts architecture relied on historic local and regional influences to ensure that each house would wholly be a product of its place. Looking back to earlier examples of Scottish domestic architecture, Charles Rennie Mackintosh intended his 1903 Hill House, in Helensburgh, Dunbartonshire, Scotland, to connect with the Scottish medieval past through a re-use of medieval and local forms. Like that at the Red House, Hill House’s facade is plain, with limited applied ornament. The exterior consisted of smooth stucco with low, protective eaves; deep windows and porches; and buttresses that were borrowed from nearby examples of the medieval country church. Inside, Hill House embodied the same idea of a total work of art in its consideration of all aspects of the space. Dark wood shaped in simple and linear forms decorated the walls, while the beams supporting the upper stories were left open to view. Handcrafted furniture and plain, white walls created a cozy effect, while the lighting filtered through wooden screens and lampshades to warm the room. Mackintosh’s appreciation for the materials and his honest expression of the structure through planar forms made Hill House fully represent the goals of the Arts and Crafts movement.

The Arts and Crafts movement had greater impact on craft than on architecture, as craftsmen were encouraged to incorporate many different artistic media into a single product. Many Arts and Crafts designers worked in groups or partnerships, with each partner specializing in a different process, such as printing or metalwork. Morris’s firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company, founded by Morris in 1861, serves as an excellent example of this diversity, as the firm could produce wallpaper, furniture, murals, stained glass, carvings, metalwork, and tapestries. The inclusion of different artistic media not only added to the overall effect of the Arts and Crafts interior but also recalled the idea of a medieval system in which different artists worked together, each providing an essential and necessary component that enhanced the overall product.

The Arts and Crafts ideology and aesthetic was not limited to English and Scottish designers. The reform efforts of Ashbee, Lethaby, Morris, and Mackintosh resonated with designers of other nations, many of whom struggled with the issue of artistic national identity, the impact of the machine on society, and the economic effect of mechanized art. Each nation, however, tended to isolate and incorporate different aspects of the ideology of the Arts and Crafts movement as they related to each nation’s context. In the United States, for example, Morris’s ideas were complemented by the efforts of Gustav Stickley, who promoted an agenda similar to Morris’s through his magazine, The Craftsman . For Stickley, a return to a handcrafted aesthetic not only promoted art and social reform but also educated the public and provided many with the means to earn their own living. Unlike the English Arts and Crafts leaders, Stickley was less concerned with evoking a medieval atmosphere in his designs, especially because the medieval did not have a connection to the American past. Instead, Stickley argued that the simple Arts and Crafts aesthetic could enhance the social conditions of the worker. As a result Stickley chose to harness the power of the machine in favor of the worker rather than at the worker’s expense. Ultimately, Stickley’s more famous designs, such as the 1903 Morris chair, were produced by his own workers using machine technology.

Outside of Stickley’s magazine and furniture empire, other American designers worked to apply Arts and Crafts principles to American design. One team of designers, Charles Sumner Greene and his brother, Henry Mather Greene, experimented with native materials in the design of the 1908 David B.Gamble House in Pasadena, California. Aesthetically, the Gamble House explored craftsmanship through a new venue that merged nature with handcraft, such that the Gamble House expressed its total work of art through a strong connection between building and landscape. In contrast to the Greene Brothers’ design is the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, who used machines to create a similar effect. The Robie House (1908) in Chicago is an example of Wright’s efforts to use simple forms and low-hanging eaves to evoke a sense of movement between parts. Like most other Arts and Crafts designers, Wright carefully considered the appearance of the interior, using rich materials and patterns to create a sumptuous yet planar aesthetic. Although Wright’s interiors relied on machines for their production, his interest in promoting a unified interior and the straightforward use of natural materials resembled ideas from the English Arts and Crafts leaders.

Like American designers, European designers placed more and less emphasis on different aspects of the Arts and Crafts ideology. In Belgium and France, the Art Nouveau movement, spearheaded by Samuel Bing, Victor Horta, and Hector Guimard, sought to strike a new balance between modernity and handcraft through an emphasis on naturalistic forms. In Barcelona, Spain, Antoni Gaudí explored regional identity through the native materials he used to create an imaginative and unique architectural style. Likewise, in Austria, the Vienna Secession movement, under the leadership of Otto Wagner, advocated an artistic break from the past and experimented with simple forms and planar volumes. All the products—art, architecture, and crafts—produced by French, Belgian, Spanish, and Viennese designers in these movements borrowed from the Arts and Crafts ideology, even if their work resulted in vastly different forms.

By 1914 the Arts and Crafts movement had faded from the architectural scene, and new ideas moved into its place, taking English, American, and Western European designers into the machine aesthetic and the International Style. Scholars recognized that the Arts and Crafts movement had important links with the Modern movement, which had first promoted the idea that architecture could reform society. Some designers, such as Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright, had direct connections with Arts and Crafts ideology and partook in the Arts and Crafts revolution of form, helping to refocus artistic production from its classical roots to its modern agenda. Without the simplicity of the Arts and Crafts movement and its emphasis on social reform, the Modern movement would have lacked a certain strength and vigor. The Arts and Crafts movement represents an important precursor to subsequent movements and the development of new forms for architectural production.

CATHERINE W.ZIPF

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1859, Philip Webb’s Red House, Kent, UNITED KINGDOM, William Morris |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1859, Philip Webb’s Red House, Kent, UNITED KINGDOM, William Morris |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1862, The Red House, Sideboard, Philip Webb |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1875, Watts Sherman House, Newport, Rhode Island, Henry Hobson Richardson |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1892-1892, The Drawing Room, Standen, UNITED KINGDOM, Philip Webb |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1887, Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton,UNITED KINGDOM, Edward Ould |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1887, Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton, UNITED KINGDOM, Edward Ould |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1890 – 1893, Covered soup tureen and ladle, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, designed by Charles Robert Ashbee, Guild of Handicraft Ltd. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1892 – 1904, Armchair, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Ernest William Gimson |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

about 1895, Pair of jugs, designed by Arthur Stansfield Dixon, made by Birmingham Guild of Handicraft |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

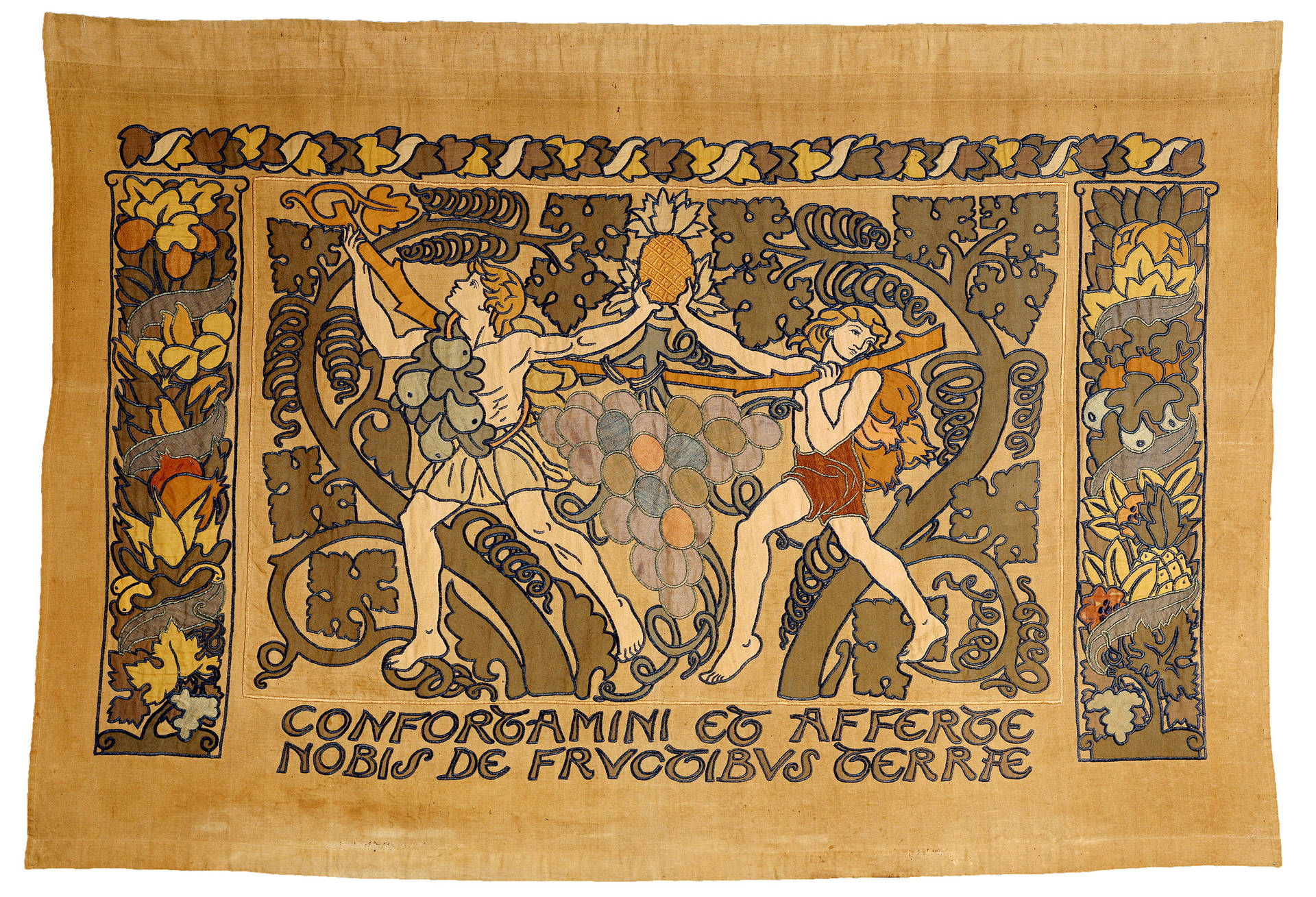

about 1900, The Spies, panel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, designed by Godfrey Blount, embroidered by Haslemere Peasant Industries |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

about 1900, Vase, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, William Howson Taylor |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1901, Ward W. Willits House, Highland Park, USA, Frank Lloyd Wright |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1901, Watercolour, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Fleetwood C. Varley |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1902, Wardrobe, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, designed by Ernest Barnsley, manufactured by Daneway House Workshops |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1903, Hill House, Helensburgh, UNITED KINGDOM, Charles Mackintosh |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1903–1906, Table, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Charles Voysey |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1905, Stoclet Palace, Woluwe-Saint-Pierre, Belgium, Josef Hoffmann |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

about 1907, Chair, Scotland Museum, designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, made by Francis Smith |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1908, David B.Gamble House, Pasadena, USA, Greene & Greene |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1908, the David Gamble house, Pasadena, USA, Greene & Greene |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1908, The Robie House, Chicago, USA, Frank Lloyd Wright |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

ASHBEE, C.R.

MACKINTOSH, CHARLES RENNIE

WILLIAM MORRIS

WRIGHT, FRANK LLOYD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1859, Philip Webb’s Red House, Kent, UNITED KINGDOM, William Morris |

| |

|

| |

1859, Philip Webb’s Red House, Kent, UNITED KINGDOM, William Morris |

| |

|

| |

1903, Hill House, Helensburgh, SCOTLAND, Charles Mackintosh |

| |

|

| |

1908, David B.Gamble House, Pasadena, USA, Greene & Greene |

| |

|

| |

1908, The Robie House, Chicago, USA, Frank Lloyd Wright |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Gaudí, Antoni ; Gropius, Walter ; Horta, Victor ; Mackintosh, Charles Rennie;Wright, Frank Lloyd

FURTHER READING

A good overview of the movement and the crafts it produced appears in Naylor 1989. Cumming includes a more theoretical description of the ideas involved in the production of Arts and Crafts goods. For biographical information on Morris, see Stansky. For biographical information on Stickley, see Sanders. For women’s participation in the Arts and Crafts movement, see Callen.

Anscombe, Isabelle, Arts and Crafts Style, New York: Rizzoli, and Oxford: Phaidon, 1991

Bowman, Leslie Greene, American Arts and Crafts: Virtue in Design, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Boston: Bulfinch Press/Little Brown, 1990; London: Bulfinch/Little Brown, 1992

Brooks, H.Allen, The Prairie School: Frank Lloyd Wright and His Midwest Contemporaries, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972; New York: Norton, 1976

Callen, Anthea, Women Artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, 1870–1914, New York: Pantheon, 1979; as Angel in the Studio: Women in the Arts and Crafts Movement, 1870 –1914, London: Astragal, 1979

Clark, Robert Judson (editor), The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1876–1916, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972

Coote, Stephen, William Morris: His Life and Work, London: Garamond, 1990; New York: Smithmark, 1995; Cumming, Elizabeth, and Wendy Kaplan, The Arts and Crafts Movement, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991

Davey, Peter, Architecture of the Arts and Crafts Movement, New York: Rizzoli, 1980; as Arts and Crafts Architecture, London: Architectural Press, 1980

Kaplan, Wendy (editor), “The Art That Is Life”: The Arts and Crafts Movement in America, 1875– 1920, Boston: Little Brown, 1987

MacCarthy, Fiona, William Morris: A Life for Our Time, London: Faber and Faber, 1994; New York: Knopf, 1995

Morris, William, News from Nowhere and Other Writings, London and New York: Penguin, 1993

Naylor, Gillian, The Arts and Crafts Movement: A Study of Its Sources, Ideals, and Influence on Design Theory, London: Studio Vista, and Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1971; new edition, London: Trefoil, 1990

Naylor, Gillian, et al., The Encyclopedia of Arts and Crafts: The International Arts Movement, 1850–1920, New York: Dutton, 1989

Sanders, Barry, A Complex Fate: Gustav Stickley and the Craftsman Movement, New York: Wiley, 1996 Stansky, Peter, Redesigning the World: Will iam Morris, the 1880s, and the Arts and Crafts, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1985

Stickley, Gustav, Craftsman Homes, New York: Craftsmen, 1909; reprint, Skyhorse Publishing, 2009

Stickley, Gustav, More Craftsman Homes, New York: Craftsmen, 1909; reprint, Dover Architecture, 2012

Trapp, Kenneth R. (editor), The Arts and Crafts Movement in California: Living the Good Life, New York: Abbeville Press, 1993 |

| |

|

|